Thursday, February 18, 2010

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Rage Rage Against the Dying of the Right. By Which I Mean Left.

It felt good. We'll give to individuals, not to any umbrella organizations. I can read polls as well as the next guy.

Monday, February 15, 2010

Canon Restores an Old Man's Faith. For a Moment.

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Friend Richard Anderson said that my camera has the very problem his Canon fell victim to a while back, but that the company was ready to repair the problem, no matter how old the camera. A quick click on the proper link, and I was soon reading the following:

Thank you for contacting Canon product support. We value you as a Canon customer and appreciate the opportunity to assist you. I am sorry to hear that your A95 camera is displaying symptoms of the CCD sensor failure.

It has recently come to our attention that the vendor-supplied CCD image sensor used in this Canon digital camera may cause the following malfunction: When the product is used in recording or playback mode, the LCD screen and/or electronic viewfinder may exhibit either a distorted image or no image at all. While reports of this malfunction have been rare in the United States, we have determined that it may occur if the product is exposed to hot and humid environments.

Based on the information you have provided, it appears that you may have encountered this issue...

They say send it back on their nickel. I am unaccustomed to so ready an embrace of responsibility from a manufacturer.

The Long Slow Slow Long Slowlonglongslow Death of American Journalism

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Whatever Happened to Shoe-Leather Reporting?

Most journalists said that social media were important or somewhat important for reporting and producing the stories they wrote.

| Importance of Social Media to Journalists (% of Respondents) | |

| Degree of Importance | % of Respondents |

| Important | 15% |

| Somewhat Important | 40% |

| Neither Important nor Unimportant | 16% |

| Somewhat Unimportant | 16% |

| Unimportant | 12% |

| Source: Cision Social Media Study, October 2009 | |

The groups placing the highest levels of importance on social media for reporting and producing stories were journalists who spend most of their professional time writing for Websites . Those at Newspapers ;and Magazines reported this less often. The differences between Magazine journalists and Website journalists is statistically significant.

- Journalists who spend most of their professional time writing for Websites (69%) reported this the most often, and significantly more so than those at Magazines (48%)

- 89% of journalists reported using Blogs for their online research. Only Corporate websites (96%) is used by more journalists when doing online research for a story

- Approximately two-thirds reported using Social Networking sites and just over half make use of Twitter for online research. Newspaper journalists (72%) and those writing for Websites (75%) use Social Networking sites such as LinkedIn and Facebook for online research significantly more often than those at Magazines (58%)

While the results demonstrate the fast growth of social media as a well-used source of information for mainstream journalists, the survey also made it clear that reporters and editors are acutely aware of the need to verify information they get from social media.

- 84% said social media sources were "slightly less" or "much less" reliable than traditional media

- 49% say social media suffers from "lack of fact checking, verification and reporting standards

Heidi Sullivan, Vice President of Research for Cision, says "Mainstream media have hit a tipping point in their reliance on social media for their research and reporting...however... it is not replacing editors' and reporters' reliance on primary sources, fact-checking and other traditional best practices in journalism."

According to the survey, most journalists turn to public relations professionals for assistance in their primary research:

- 44% of editors and reporters surveyed said they depend on PR professionals for "interviews and access to sources and experts"

- 23% for "answers to questions and targeted information"

- 17% for "perspective, information in context, and background information"

Don Bates, founding director of the GWU Strategic Public Relations program, cautions that, though "Social media provides a wealth of new information for journalists... getting the story right is as important as ever... PR professionals... have a responsibility... to ensure the information they provide journalists is accurate and timely... "

For a copy of the complete survey results, please go here.

Sunday, February 14, 2010

Salon Dry Run: A Visit to Nancy in Crockett

Sigh. Our camera has a sensor problem so a number of photos didn't come out. But the general thrust of the experience is captured: visit, eat, drink, hear poetry, hear jazz.

Take my word for it.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

Two Thoughts to be Thought about Some More Regarding Arts Reviewing

* If I were to set up as an anonymous reviewer, my nom would be Anatole Imho.

Friday, February 12, 2010

King of Newspaper Sociologists Big Mike Schudson Fills the Air with Hope

This from deep in the piece, his fifth reason for hope.

The new online operations remind us how important is the resource of obsessive, endless, gritty enthusiasm. Yes, somehow there has to be a way for these individuals to pay their bills – ultimately. They don’t have to dine on expense accounts. What they have to do is pursue work that gets their adrenalin going and makes them feel that they are doing something that matters. If they can make money doing this, that’s good for them and that’s good for society and that’s good for democracy. But many worthwhile pursuits endure without a so-called business model. Artists, musicians, dramatists have been doing it for centuries. And so have some journalists, those who set up their alternative weeklies in the sixties, those who worked for political magazines or started vegetarian newsletters or pieced together a living as free-lance foreign correspondents. They lived on a combination of passion and lowered expectations for comfort. With just about everyone I have talked to at the new start-ups, whether twenty-somethings at one of their first jobs or 50-somethings who had been let go or had taken buy-outs. One top editor from a major daily newspaper, now working at Pro Publica, told me she felt she had died and gone to heaven, that she was doing more of the work that had led her to journalism in the first place than at any other time in her career.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Why I Blog: A Friend Wonders

Image by Thomas Hawk via Flickr

Image by Thomas Hawk via Flickr

A friend writes:

And I reply:

Well, thanks. My blogging falls into two chunks – the first couple years when I thought it would somehow turn into something, that it would become a way into other writing opportunities. (I wasn’t exactly sure how. I imagined something I wrote would go viral, and the rest would unfold with iron inevitability.) After I realized that wouldn’t happen, I thought the blogging would wither away. But I found I still liked to do it because it was a creative release – and I don’t have one, or maybe I should say I am too lazy to work at *really* writing something and getting it published.

For real. For money.

Because I keep track of the number of my daily visitors and how they are referred to my blog, I have a keen sense of how my readership has dropped. Five years ago when I was writing long and posting frequently, I was able to drive my daily visits up to 100. But since then, I have seen the daily hit rate steadily drop to about 20, the majority of whom are accidents, not regular visitors. This is oddly liberating. The fact I am throwing my words out into the void seems brave/ironic/self-consciously futile. No one is reading me *but I soldier on anyway*.

If I described my justifications tomorrow, I would probably describe them very differently. My rationale is variable. But the truth is that I get some kind of sensation out of writing to no one – maybe it’s a kind of “lottery ticket” thing: Knowing you won’t win doesn’t mean you can’t win if you know what I mean, though I should probably say if you *feel* what I mean.

It’s odd. My blog is a kind of commonplace book that helps me keep track of the march of time. (Now that I’ve plugged Twitter into the blog, it’s even more so.) It’s also a personal journal that justifies the effort of typing, not writing by hand, by the fact what is so neatly typed is published – sort of. In fact, one of the pleasures of my blog is all the little “self-publishing” flourishes, all the links and pictures and debris I can throw against the wall.

Somehow it shows I haven’t given up. Well, actually I have. But this is my “apron of leaves.” If I were to blog this, I could link to the quote and maybe to a picture.

I think I *will* blog this. (Maybe the multi-purposing is part of the draw.)

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

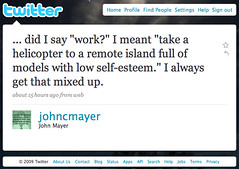

My Students Aren't Quite Sure about My Making Them Use Twitter

Image by johanneskr via Flickr

Image by johanneskr via Flickr

Today, I sent them this message:

John Mayer could only love a woman who uses Twitter.

He said he still loved Aniston, but then noting their age difference (she just turned 41), he said: "I can't change the fact that I need to be 32."

He also said she didn't appreciate new technology: "The brunt of her success came before TMZ and Twitter. I think she's still hoping it goes back to 1998. She saw my involvement in technology as courting distraction. And I always said, 'These are the new rules,"' he said.

It's from ... I've lost where it's from! Sorry.

This from WSJ:

(Read Mayer’s updated apology Twitter stream.)Saturday, February 06, 2010

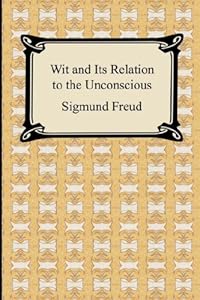

Why Do People Laugh? I Turn a Ripoff into a Tipoff for My Reviewing Students

Cover of Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious

Cover of Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious

1) Much disagreement exists about the nature of laughter. That disagreement probably reflects the fact that contradictory ideas about laughter are part of the tension between fundamental ways of looking at the world. Thinking about laughter is a small corner of much larger arguments about much larger philosophical differences.

2) The fact deep thinking about laughter has already been done makes it easier for us, not harder. Someone has already done the heavy lifting! If we find some theoretical insight that seems to give us a better focus on something that makes us laugh (or fail to even though it’s supposed to be funny, we are told) we can use it without trying to justify the insight, though we would certainly present examples from the thing being reviewed. We might write: “I read somewhere that laughter is …, and that helps me make sense of….”

3) Obviously, you can’t do too much of this if you are doing a relatively short review for a relatively broad audience. You are writing a review, not a scholarly treatise. You might educate your audience a little, but you don’t talk down to your audience.

4) Some of the following material I don’t understand by which I mean that I could not possibly put it into my own words. It’s not that I disagree with it; I just don’t get it. Be careful about tossing in jargon for its own sake. You are essentially saying of one or more of the following ideas: You know? That makes sense to me. It puts words to my feelings.

Introduction – Excerpts from The Nature of Laughter, which you can see online at

http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/kincaid2/intro2.html

James R. Kincaid, Aerol Arnold Professor of English, University of Southern California

Some excerpts

One unavoidable issue, however, appears in most theoretical analyses of laughter and must be dealt with before a more general discussion can be attempted: the degree to which laughter expresses (if it does at all) hostility, aggression, the vestiges of the jungle whoop of triumph after murder, and other unpleasant impulses. The corollary to this issue is the debate over whether laughter is incompatible with sympathy, geniality, or indeed with any emotion. (MR: Interesting. Is there such a thing as friendly laughter? Are we laughing at Michael Scott or with him? ) Roughly speaking, the dark-laughter theorists spring from Thomas Hobbes; the genial-laughter theories from Jean Paul Richter. Without retracing the steps of this very tortuous, often confused, and usually truculent argument, one can, I think, accept the reasoning of Arthur Koestler, which is based on the simple fact that nearly all the important writers on the subject have, [9/10] for hundreds of years, noted "a component of malice, of debasement of the other fellow, and of aggressive-defensive self-assertion . . . in laughter -- a tendency diametrically opposed to sympathy, helpfulness, and identification of the self with others" (p. 56) I find this argument and the evidence given by the theorists cited above (see note 24) conclusive…. (MR: Sounds like Kincaid is a “laughing at” guy.)

One of Henri Bergson's most important distinctions, which, if noticed, would silence almost all of his critics, applies here. After arguing that "laughter has no greater foe than emotion", he adds, "I do not mean that we could not laugh at a person who inspires us with pity, for instance, or even with affection, but in such a case we must, for the moment, put our affection out of court and impose silence upon our pity" (p. 63). (MR: So in the moment we have contempt for someone but later on, in another moment, we might forgive his stupidity??? I might be able to do something with this idea in a TV sitcom review.) The key phrase is "for the moment"; our ordinarily active sympathy is temporarily withdrawn in the process of laughing….

Bergson sees the basis of all laughter in the conflict of the rigid and mechanical with the flexible and organic; the key is "something mechanical encrusted on the living" (p. 84). He sees laughter as, above all, a "social gesture" (p. 73), the corrective by which society humiliates in order to preserve itself from the deadening effects of what Matthew Arnold called "machinery" -- political, ideological, social, and psychological rigidity. Therefore, "we laugh every time a person gives us the impression of being a thing" (p. 97) and, of course, at the converse. (MR: Might this have something to do with the ridiculousness of someone who doesn’t learn from experience? “Satire” is an interesting idea if you define it as ridicule that is supposed to promote change.)

(This theory is consistent with) a vision of human beings fundamentally isolated from one another and from their environment, but also because of laughter as a rhetoric tool to enlist (the audience) in a protest against isolation and mechanistic dominance, and in support of imaginative, sympathy and identification with others….

Bergson's clarity and lucidity become simplistic if stretched too far, and one is forced to turn to more subtle and complex theorists, principally Freud. Freud's work on laughter, though by no means universally accepted, comes about as close to that position as any single statement reasonably could. (MR: Freudianism was still quite a big deal as a tool for literary analysis when I was in school. But I thought that wasn’t true anymore. Reminder to self: Ask chum in English department.) More important, his concept of laughter is far more flexible and inclusive than most, and takes into account two factors in laughter that are often separated and treated as exclusive: the offensive release of aggression, hostility, or inhibition and the defensive protection of pure pleasure, joy, or play. Though the complexity of Freud's argument makes it extremely difficult to summarize (there is, however, a successful and extremely useful summary and clarification by Martin Grotjahn), a brief discussion is essential.

The major part of Freud's work on laughter was published [11/12] in 1905 under the title, Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious…. He begins with wit, that form of producing laughter which functions most like dreams, and shows that it originates in aggressive or obscene tendencies. The aggressive or obscene idea is activated in the unconscious but disguised by the wit-work (or technique) so that the psychic energy initially aroused can be safely relieved. (MR: Sounds good. Not quite sure what it means.) If the joke is successful, the source of laughter in the teller and the listener is the same: "the economy of psychic expenditure" (p. 180), or in other words, the efficient use of energy previously needed for repressing the dangerous idea by removing the apparent danger and releasing the energy in laughter. In addition to the pleasure aroused from release, there is also play pleasure: the infantile and pure joy in nonsense, playing with words, and combating order. To summarize to this point, then, jokes can be analysed as to technique and tendency, though it is likely that the technique in most cases is mainly the disguise and the tendency the cause of the laughter. We laugh because we are permitted to express the energy from hostility or aggression openly; the release plus the infantile joy of word play account for the pleasure in laughter. (Robertson’s emphasis added)

By far the least important and persuasive part of Freud's analysis follows, an account of our pleasure in the comic. Here Freud discusses the laughter at stupidity, the naive, caricature, repetition, and the like, explaining it as differing from wit in its psychic location (foreconscious rather than subconscious), [12/13] in its moving beyond words into action and behaviour, and in the fact that it is based on an explicit comparison of ourselves with another's limitations. The pleasure in this case is provided by the feeling of superiority, (MR: Pretty obvious, right?) as Hobbes had said, plus a release of inhibition energies temporarily unnecessary in the face of such childish action. Freud remarks on his indebtedness to Bergson at this point, and Bergson is clearer and more satisfactory in this area.

Both wit and the comic, Freud argued, are incompatible with strong emotion (p. 371), which is one reason why they must be presented in a disguised form. In the final section of the book, supplemented by a paper published in 1928 ("Humour", International Journal of Psychoanalysis, cited as IJP) Freud discusses humour, which he describes as a way of dealing with pain. His best example of humour concerns the prisoner on the way to the gallows who remarks, "Well, this is a good beginning to the week" (IJP, 1). For the prisoner, this comment represents a way of combating pain by denying its province; it is the rebellious assertion by the ego that it is invulnerable (IJP, 2-3). More important, the pleasure for the listener is derived from an "economy of sympathy" (Wit, p. 374). We are prepared to respond with pity, but pity is found to be superfluous and the energy first called up for sympathy can be released in laughter. More generally, he speaks of the "economized expenditure of affect" (Wit, p. 371), in which the energies associated with any strong emotion are aroused, then shown to be unnecessary, and are thereby available for laughter. (MR: Fascinating. Not sure how it would apply to sitcom humor.)

Actually, Freud recognized quite clearly that his categories were analytical conveniences and that, in practice, wit, the comic, and humour were intermixed. For our purposes, the most important uses of Freud will be: the distinction between technique and tendency, and the general dominance of the latter as a cause of laughter; (MR: Don’t quite understand what the preceding phrase means) the dual pleasure source of laughter; and the concept of economy and its explanation of the way in which aggression, inhibition, and strong feelings of sympathy or fear can be turned into laughter. (MR: I think I get this part, at least the aggression and inhibition part.)

This is the general outline, then, of the approach to laughter to be used here. It does not, of course, constitute a complete theory of laughter, and it is perhaps incomplete because it [13/14] concentrates almost entirely on the laugher to the exclusion of the means of evoking laughter. An appropriate (at least forceful) apology for both limitations is offered by Samuel Johnson, who chides "definers" of comedy for having fiddled with useless definitions of techniques of arousing laughter "without considering that the various methods of exhilerating [the dramatist's] audience, not being limited by nature, cannot be comprised in precept" (iii, p. 106) (MR: Yeah. Sometimes we can talk profitably about how the comic bit works. I once interviewed a group of standup comics, and they spent a half hour talking about which numbers are funny and which aren’t.)

To supplement, in a minor way, the arguments of Bergson and Freud, a few subsidiary points should finally be considered:

i. Laughter and order. One of the reasons laughter has always been identified in some way with the form of comedy is that their main impulses are similar: the restoration of order or equilibrium. (MR: I remember this from grad school. I think one of the implications was that much/most comedy is “conservative” and not revolutionary. You would certainly figure that would be true of network TV.)

Behind comedy lie the ritual pattern of resurrection (see Cornford; and Frye, pp. 212-15) and the movement to a new society; though the origin of laughter is not so clear, certainly one of its functions is the restoration of "social equilibrium" (this is the central thesis of Ralph Piddington). Paradoxically, the movement towards order is paralleled by an impulse towards freedom. (MR: But which force predominates? In The Office, no one ever escapes! Right?) Like comedy, which progresses "from law to liberty" (Frye, p. 181), laughter moves from restraint to release and from a world of mechanistic restriction to a world of childhood and play. Though we laugh always in chorus, either real or imagined, the society we create by our laughter is generally opposed to what we ordinarily think of as society; in the desire to cleanse the existing order of absurdity and rigidity, laughter is always dangerously close to anarchy. This is only a way of saying that laughter is a means of having it both ways: it reassures us of our social being (we are part of a chorus), but also, and perhaps more basically, of our own invincible and isolated ego. (MR: Pretty good. Sounds rather manipulative, doesn’t it?) Thus laughter both confirms and denies society and is, from a social viewpoint, implicitly subversive. It moves towards a coalition, but it is a coalition of joyful people dedicated to freedom and play; order is, at best, secondary. (MR: Does this sum up The Office? Or is it just the opposite. Pop. That’s the sound of my mind being blown.)

ii. Vulnerability and immunity provided by laughter. Laughter provides a kind of immunity which may become a special kind of vulnerability. Laughter implies the sort of commitment which is so complete that it is unable to avoid rebuffs; it assumes complicity and sanctity and is therefore especially vulnerable to attack, as anyone knows who has had his own laughter met with icy stares. Having released the energies ordinarily used to guard our hostilities, inhibitions, or fears, we are especially unprotected if the promised safety which allowed us to laugh proves to be illusory. Imagine the fat old man who slipped on the banana peel being suddenly identified as our brother, now seriously hurt; the custard pie containing sulphuric acid; the train really hitting the funny car and killing the Keystone Cops. (MR: Embarrassing example, but I suddenly think of Ben Affleck being killed in Smokin’ Aces. Ugly movie, but I kept watching.)

iv. Laughter and the narrative. Our laughter is conditioned not only by memory but by anticipation of the future. The expectation of a happy ending can induce a mood of comfort or euphoria particularly suited to laughter; conversely, the anticipation of a sad or frightening ending makes us seize all the more readily on nearly any excuse to laugh. (MR: Well, there you go. You are safe, Michael Scott. My wife is always saying, “She’s going to die!” And I’m always saying, “She’s the co-star. The co-star does not die.” But if you are a Star Trek “red jacket…!” Tonight you dine in hell.)

Thursday, February 04, 2010

I Think I Made a Mistake

Dunder-Mifflin, the fiction..." Image via Wikipedia

Dunder-Mifflin, the fiction..." Image via Wikipedia

Anyway, the discussion never quite recovered from my saying I hated reality shows -- bad teacher; shut uuuup -- and we settled on the U.S. version of The Office, which I like for reasons I will post about when the kids have done their reviews. Tonight's episode was ground zero, and it was a transitional episode, not all that funny, filled with plot business to set up new situations and new conflicts to keep the gears turning.

One of the amusing ideas in TV criticism is The Jumping of the Shark, that moment when a long-running show has a character or characters do something that represents not invention but creative exhaustion, that moment from which there is no recovery.

Has The Office jumped the shark this season? I'm going to have to think about that.

If you are invested in the Office characters, you're are glad -- at least, provisionally -- that there's some new angst in the series collective pants. Kathy Bates is the new boss (with a Southern accent) because there's been a buyout, and buyouts are in the news, or at least were in the news a year or two or three -- okay, a president -- ago. Maybe there will be a new twist on the sitcom's preferred trope -- Steve Carell's nonsense vs. someone else's no-nonsense.

Actually, there's been very little no-nonsense in any of The Office's subordinate characters, which has taken the edge off Michael Scott's obnoxiousness. (I think this is an important difference between U.S. Office and the U.K. original, where Ricky Gervais really did make me cringe, sometimes with sympathy.)

We'll see. The students who have never seen the show must be wondering where the charm lies. I'll push back the due date and let them fold in next week's episode. If I were a new viewer, I'd lay my hands on the first couple episodes and do a little comparison and contrast, not to mention dragging in a little Marxist analysis of how subversive entertainment often isn't.

There's room, young people. There's opportunity. When in doubt, snark.

Tuesday, February 02, 2010

Jesus Is the Real Catcher in the Rye

When I defended HC, I am proud to say I did not mention in passing, as a good WJBC student might, that Holden's real problem -- once we'd cleared away all the literary rubbish -- was that he had not accepted Jesus Christ into his heart. I certainly heard that kind of comment about all sorts of people, real and fictional, during my college days. Sometimes I think the bad students did it as way of distracting their teachers.

Even though I still had a kind of "half faith" early in my college days, I did understand that in J.D. Salinger's world there was no saving Jesus, that it would have ignored the implicit nature of his fictive universe to push Jesus into it. He just wasn't there, and it would have been stupid to bring him up.

I will give credit to English professor Herbert Lee, who liked my Catcher essay and who always respected the text and always approached the books we studied on their own terms. Nor did he ever step back from the works and suggest that their fictional universes were inauthentic in that they created from a flawed premise in that their writers were not (as they should be) fundamentalist Christians.Without ever saying so, he was pretty much telling us that there was more than one way to look at the world, and more than one way to deal with its problems or to despair at dealing with them. He did not allow us to condescend to the secular world. We did not smugly read.

He was, of course, an Episcopalian. I never risked asking him how he ended up at WJBC. I guess he needed the work.

He was somewhat short on charisma, and I hadn't thought of him in years, but I am reminded that he was no fool. He didn't play at being a teacher. He really was one. If 50 years from now one of my students remembers me with just such a momentary simmer of regard, that would be pretty good. You don't know. You just keep plugging. That's what Herb Lee did. That's what it looked like, anyway.

Monday, February 01, 2010

Holden as in Holdin' Those Children; Or Listening to NPR during Drive Time

Well, of course, I read Catcher. I can even tell you the year. It was 1962 at Whooping Jesus Bible College, where it wasn't assigned, but I wrote about it anyway for freshman English. Professor Herbert Lee said I made a strong case for the appropriateness of the profanity in the book, and that it changed his attitude. If so, that was a compliment. I guess it was a compliment even if not so.

I did not write in freshman English about the secret pleasure the book gave me, a pleasure of a type I have since read is provided to women living hard lives when they read in the tabloids about the tragedies of the Hollywood stars. These stars are rich and famous, but they suffer just like me, the women are supposed to think. Indeed, they suffer more than I do, and it cheers the women up about their relative status.

That was one of the pleasures I found in Catcher in the Rye. Life in boarding schools and in New York City seemed infinitely alluring. I was pretty sure that any problems Holden had would be temporary, and that even if somehow he were busted down to a relatively ignominious life, even in ignominy his life would be something I could only dream of.

If he slid down the mountain, I was pretty sure he would catch on a branch higher than I would ever be able to climb. I wasn't stupid about the advantages of privilege even though my familiarity with New York society came from Ellery Queen detective stories.

Of course, I admired the book's clumsy conversational tone that came out eloquent because it was so artfully artless. I got that even if I didn't quite understand how to do it. I figured it was the inarticulateness of the rich and powerful, just another one of their codes. So there's the simple truth. I was secretly comforted by the travails of the privileged. I wanted to identify with Holden but couldn't quite. The preppie had problems the peasant could only envy, classy problems (in the Marxist sense) to which I could only aspire.

You find what you need in the good books, even if those needs are shame and envy.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=fa17ea9a-d949-437b-a9ef-a678b9a05d22)

Reblog this post [with Zemanta]">

Reblog this post [with Zemanta]">![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=cc676638-1d14-45c4-9938-3cb8354c0e21)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=edb3c7d1-ab00-460b-86e2-89a264547ea8)

Reblog this post [with Zemanta]">

Reblog this post [with Zemanta]">![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a66e77c8-6d54-4df3-865e-58b6daceee7e)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=483f5e41-e6cd-41f5-b991-724f65e9771f)

Reblog this post [with Zemanta]">

Reblog this post [with Zemanta]">![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7acadfe8-4ae8-425d-8eaa-aab027a66241)